Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium is a foundational principle in population genetics, offering a baseline for understanding allele and genotype frequencies.

Numerous Hardy-Weinberg practice problems and solutions are available in PDF format, aiding comprehension of these calculations.

These resources demonstrate applying the equations to real-world scenarios, like genetic conditions and blood type distributions within populations.

What is Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium?

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium describes a theoretical state where allele and genotype frequencies in a population remain constant from generation to generation. This stability isn’t indicative of a lack of evolution, but rather a condition where evolutionary forces aren’t actively altering the genetic makeup. Understanding this principle is crucial when tackling Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems and solutions, often found in PDF study guides.

Essentially, it provides a null hypothesis – a baseline against which to measure evolutionary change. If observed frequencies deviate from those predicted by the Hardy-Weinberg equations, it suggests that evolution is occurring. Many resources, including downloadable PDFs, present example problems, such as calculating carrier frequencies for recessive genetic disorders like Cystic Fibrosis (occurring at a rate of 1 in 10,000).

These problems and solutions illustrate how to utilize the equations to determine allele frequencies and assess whether a population is in equilibrium. The core concept revolves around predictable genetic ratios under specific conditions.

Assumptions of Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium rests on five key assumptions, rarely met perfectly in natural populations. These conditions are vital when working through Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems and solutions, often detailed in PDF resources. First, there must be no mutation. Second, there should be random mating – individuals choose mates without regard to genotype. Third, there’s no gene flow – no migration of individuals into or out of the population.

Fourth, the population must be large – minimizing the effects of genetic drift. Finally, there’s no natural selection – all genotypes have equal survival and reproductive rates. Deviation from any of these assumptions can disrupt equilibrium.

PDF guides containing problems and solutions frequently highlight how these assumptions are tested and the implications of their violation. For example, problems involving lethal recessive conditions demonstrate how selection pressure impacts allele frequencies, moving the population away from equilibrium.

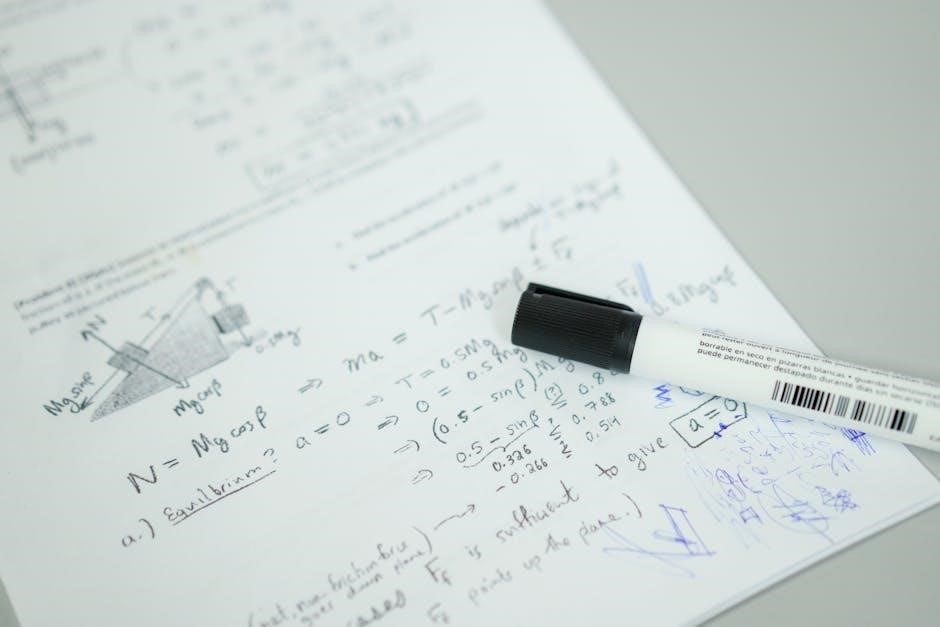

The Hardy-Weinberg Equations

Hardy-Weinberg Equations are central to solving Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems, often found in PDF study guides. These equations mathematically define allele and genotype frequencies.

Understanding these is key!

The Genotype Equation: p² + 2pq + q² = 1

The equation p² + 2pq + q² = 1 represents the distribution of genotypes within a population at equilibrium, frequently utilized in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems available as PDF resources.

Here, ‘p²’ signifies the frequency of homozygous dominant individuals, ‘2pq’ denotes the frequency of heterozygous individuals, and ‘q²’ represents the frequency of homozygous recessive individuals.

These PDF guides often present problems where you’re given the frequency of one genotype (like q²) and must calculate the others. For instance, if a lethal recessive condition affects 1 in 20,000, you’d use this equation to determine carrier frequencies (2pq).

Mastering this equation is crucial for solving various genetic problems, and practice problems with detailed solutions in PDF format are invaluable for solidifying understanding. The sum of these genotype frequencies always equals 1, representing 100% of the population.

The Allele Equation: p + q = 1

The equation p + q = 1 is fundamental to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, representing the sum of allele frequencies for a given trait within a population. Numerous Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems, often found in PDF format, utilize this equation as a starting point.

‘p’ represents the frequency of the dominant allele, while ‘q’ represents the frequency of the recessive allele. Their sum must always equal 1 (or 100%), as these are the only two possible alleles for that gene.

Many PDF practice problems begin by providing the frequency of one allele (often the recessive allele, ‘q’) and task you with calculating the frequency of the dominant allele (‘p’).

This simple equation is essential for determining allele frequencies before applying the genotype equation (p² + 2pq + q² = 1). Understanding this relationship is key to successfully solving complex genetic problems, and readily available PDF resources offer ample practice.

Solving Hardy-Weinberg Problems: A Step-by-Step Approach

Hardy-Weinberg problems, often available as PDF guides, require identifying knowns, utilizing p + q = 1, and p² + 2pq + q² = 1 for calculations.

Identifying the Knowns and Unknowns

Successfully tackling Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems, frequently found in PDF practice sets, begins with meticulous identification of provided information. These problems often present data like the incidence of a recessive phenotype, or the frequencies of different genotypes within a population.

Carefully determine what the question asks you to calculate – is it the frequency of a dominant allele (p), a recessive allele (q), a specific genotype (p², 2pq, or q²), or the carrier frequency (2pq)?

Often, a problem will state the frequency of individuals expressing a recessive trait (q²). Recognizing this is crucial. Conversely, you might be given the number of individuals with a particular blood type, requiring conversion to a frequency.

Clearly listing the known values and explicitly stating the unknown variable(s) is a vital first step, preventing errors in subsequent calculations. This organized approach, emphasized in many Hardy-Weinberg practice problem solutions, ensures accuracy.

Using the Allele Frequency Equation to Find ‘q’

Many Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems, readily available as PDF practice materials, require determining the frequency of the recessive allele (‘q’) first. This is often the most straightforward starting point. If the problem provides the frequency of the recessive phenotype (individuals expressing the recessive trait), that value directly represents q².

To find ‘q’, simply calculate the square root of the recessive phenotype frequency. For example, if 1 in 20,000 individuals exhibit a recessive condition, q² = 1/20,000. Therefore, q = √(1/20,000) ≈ 0.0071.

Remember, ‘q’ represents the allele frequency, a decimal value between 0 and 1. Practice Hardy-Weinberg problems and solutions consistently reinforce this step.

Understanding this initial calculation is fundamental, as ‘q’ is then used in the subsequent equation (p + q = 1) to determine ‘p’, the frequency of the dominant allele.

Calculating ‘p’ from ‘q’

Once you’ve determined the frequency of the recessive allele (‘q’) using Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems – often found in PDF format for practice – calculating ‘p’, the frequency of the dominant allele, is remarkably simple. The foundational equation, p + q = 1, provides the direct relationship.

Rearranging the equation, we get p = 1 ⎼ q. Therefore, if you know ‘q’, subtracting it from 1 yields ‘p’. For instance, if ‘q’ was calculated to be 0.0071 (as in the previous example involving a recessive condition), then p = 1 ⎼ 0.0071 = 0.9929.

This value, ‘p’, represents the proportion of the dominant allele in the population. Mastering this step, alongside finding ‘q’, is crucial for solving a wide range of Hardy-Weinberg problems and solutions. Consistent practice solidifies this skill.

Practice Problems & Solutions: Recessive Allele Frequency

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems, often available as PDFs, frequently focus on recessive allele frequencies.

These problems test your ability to apply the equations to real-world genetic scenarios.

Problem 1: Lethal Recessive Condition in South America (1 in 20,000)

Consider a scenario in South America where a lethal recessive condition affects 1 in every 20,000 babies born. This type of problem is commonly found within Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems and solutions PDF resources, designed to illustrate practical applications of the principle.

The challenge lies in determining the frequency of carriers – individuals who possess one copy of the recessive allele but do not exhibit the condition themselves. To tackle this, we first recognize that the frequency of the affected individuals (q²) is 1/20,000, or 0.00005.

These practice problems, often presented in detailed PDF guides, emphasize a step-by-step approach to calculating allele and genotype frequencies within a population assumed to be in equilibrium. Understanding this foundational concept is crucial for comprehending evolutionary processes and genetic diversity.

Solution to Problem 1: Calculating Carrier Frequency

To calculate the carrier frequency (2pq) for the lethal recessive condition, we begin with the established q² value of 0.00005, derived from the 1 in 20,000 incidence rate. Taking the square root of q² yields ‘q’, the frequency of the recessive allele, approximately equal to 0.00707.

Next, utilizing the Hardy-Weinberg equation p + q = 1, we determine ‘p’, the frequency of the dominant allele: p = 1 ⎼ q = 0.99293. Finally, applying the 2pq formula, we calculate the carrier frequency: 2 * 0.99293 * 0.00707 ≈ 0.0140;

Therefore, approximately 1.4% of the population are carriers of the recessive allele. Numerous Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems and solutions PDF documents detail this process, reinforcing the application of these equations. These resources are invaluable for mastering population genetics concepts.

Practice Problems & Solutions: Dominant Allele Frequency

Dominant allele frequency problems utilize Hardy-Weinberg principles to determine allele proportions within a population, often found in PDF guides.

These examples, like blood type calculations, demonstrate practical application of the equations.

Problem 2: Blood Type A and O Frequencies

Problem Statement: Consider a population exhibiting Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium regarding blood types. Within this population, 56% of individuals possess blood type A, while 25% have blood type O. The task is to determine the allele frequencies for the A and B alleles responsible for the ABO blood group system.

This type of problem is frequently encountered in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems and solutions PDF resources, designed to build proficiency in applying the equations. Blood type O individuals have the genotype ‘oo’, allowing for direct calculation of the ‘q’ allele frequency (frequency of the ‘o’ allele).

Knowing the frequency of the ‘o’ allele, we can then calculate the frequency of the ‘A’ allele (‘p’) using the equation p + q = 1. Subsequently, the frequency of the ‘B’ allele can be determined, as the total allele frequency must equal 1. These calculations demonstrate a practical application of the Hardy-Weinberg principle in a real-world genetic scenario.

Solution to Problem 2: Determining Allele Frequencies

Step 1: Calculate ‘q’ (frequency of the ‘o’ allele). Since individuals with blood type O have the genotype ‘oo’, their frequency (25% or 0.25) directly represents q². Therefore, q = √0.25 = 0.5.

Step 2: Calculate ‘p’ (frequency of the ‘A’ allele). Using the equation p + q = 1, we find p = 1 ⎼ q = 1 ⎻ 0.5 = 0.5. This indicates that the frequency of the ‘A’ allele is also 0;5.

Step 3: Determine the frequency of the ‘B’ allele. Individuals with blood type A can be either ‘AA’ or ‘AO’. Since we know ‘p’ and ‘q’, we can deduce the frequency of the ‘B’ allele. However, the problem only asks for ‘A’ and ‘O’ allele frequencies.

These calculations, commonly found in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems and solutions PDF guides, illustrate how to derive allele frequencies from genotype frequencies assuming equilibrium.

Real-World Applications & Limitations

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium aids in understanding genetic variation, but real populations rarely meet its strict assumptions.

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems and solutions PDF resources highlight these limitations and practical applications.

Cystic Fibrosis Example: Calculating Recessive Allele Frequency (1 in 10,000)

Cystic Fibrosis, occurring at a rate of 1 in 10,000 within an isolated population, serves as a compelling example for applying the Hardy-Weinberg principle. This allows us to estimate the frequency of the recessive allele responsible for the disease.

Assuming Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, we begin by recognizing that the incidence of the disease (1/10,000) represents the frequency of the homozygous recessive genotype (q²). Therefore, q = √(1/10,000) = 0.01.

Numerous Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems and solutions PDF documents demonstrate this calculation step-by-step. Using the allele frequency equation (p + q = 1), we can then determine the frequency of the dominant allele: p = 1 ⎼ q = 1 ⎻ 0.01 = 0.99.

Consequently, the carrier frequency (2pq) would be 2 * 0.99 * 0.01 = 0.0198, or approximately 1 in 50 individuals. These PDF resources provide similar examples, reinforcing understanding of these calculations.

Deviations from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

While the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium provides a useful null hypothesis, real-world populations rarely meet all its assumptions perfectly. Several factors can cause deviations, indicating evolutionary change is occurring.

These include mutations, gene flow (migration), non-random mating, genetic drift, and natural selection. Each factor introduces allele frequency changes, disrupting the equilibrium. Understanding these deviations is crucial for interpreting population genetics data.

Many Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems and solutions PDF resources address scenarios where deviations are apparent, prompting analysis of the underlying evolutionary forces. For instance, identifying significant differences between observed and expected genotype frequencies suggests selection or non-random mating.

These PDF documents often include discussions on how to interpret these deviations and their implications for population evolution, offering a comprehensive understanding beyond simple calculations.